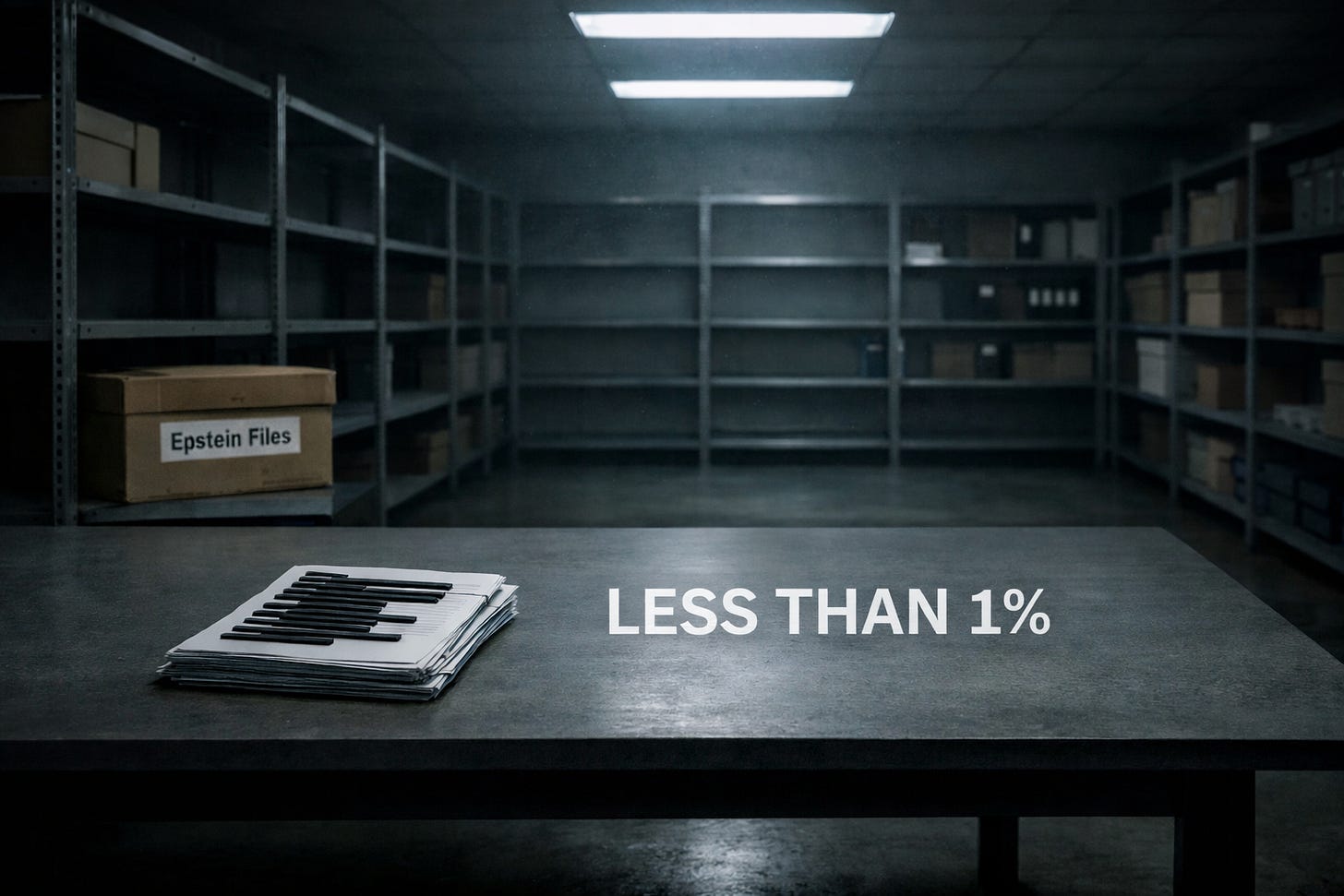

Less Than One Percent

How the Justice Department Ignored a Law Requiring Release of the Epstein Files and What That Silence Reveals About Power and Accountability

The Justice Department was required by law to release the Epstein files by December 19. It didn’t.

Instead, it quietly published less than 1% of the material it was legally obligated to make public, all highly redacted, not because Congress changed the rules or compliance was impossible, but because the department charged with enforcing the law chose not to follow it.

That isn’t a delay. It’s defiance, wrapped in bureaucratic language and sold as routine process. It sends a message that lands hard at every kitchen table in America. Transparency still stops where power begins.

Want to Know Your Rights?

Download a free digital copy of the U.S. Constitution, the same document Trump is trying to bulldoze. Learn exactly what he’s breaking, and how to fight back.

100,000+ strong — and counting.

This holiday, become a paid subscriber for just $1 a week and help us keep the truth alive.

Join The Coffman Chronicle — $1/Week

The Missed Deadline

A Deadline the Government Chose to Ignore

December 19 was not a suggestion. It was a deadline written into law.

Congress required the U.S. Department of Justice to release records connected to Jeffrey Epstein, part of a long-running effort to force transparency in a case that has repeatedly exposed how differently the justice system behaves when wealth and influence enter the room. By that date, the public was supposed to receive the bulk of the Epstein-related documents held by the department.

What it received instead was a fraction so small it barely registers: less than one percent.

It was not 1% released with a detailed timeline for the rest, nor 1% paired with an inventory explaining what remains hidden. Instead, it was just a sliver, just enough to technically claim movement, but nowhere near enough to meet the substance of the law.

This distinction matters, because the language used to describe what happened is doing work it doesn’t deserve. This wasn’t a short delay. It wasn’t an administrative backlog. A delay implies intent to comply. What happened here shows no such intent.

Less Than 1% Is Not a Delay

If an ordinary person ignored a statutory deadline this completely, consequences would follow. Fines. Sanctions. Escalation. When the Justice Department does it, the response is silence, and a hope that the public won’t notice the math.

The law did not ask DOJ to retry Epstein or reveal sensitive personal information without review. It asked for transparency, the basic democratic expectation that when the government exercises enormous power and fails spectacularly, the record of that failure belongs to the public.

Releasing less than 1% is not transparency. It is refusal disguised as compliance.

The refusal wasn’t loud. There was no press conference acknowledging noncompliance, no public explanation of why the deadline was missed, and no clear statement of when — or whether — the remaining records will be released. The department simply moved on, apparently betting that distraction, fatigue, and time would do what the law could not.

That bet only works if people accept the premise that legal obligations are optional when they become inconvenient, and that accountability is something the Justice Department enforces, not something it submits to.

This case will test whether that premise holds.

What the Epstein Files Actually Represent

These Records Are About Government Conduct, Not Gossip

The Epstein files are routinely described as if they exist to satisfy public curiosity, a trove of names, rumors, and lurid details waiting to be spilled. That framing is convenient. It’s also wrong.

These records are not primarily about Jeffrey Epstein. They are about how the government handled him.

At their core, the Epstein files are a documentary record of state power, including investigative decisions made and not made, charging strategies pursued and abandoned, and warnings received and ignored. They likely include internal communications among prosecutors, correspondence with defense attorneys, assessments of victim credibility, negotiations over plea agreements, and inter-agency exchanges that reveal how aggressively or passively the case was handled at different points.

That distinction matters, because it reframes the entire transparency question.

The public is not owed these documents because Epstein was notorious. The public is owed these documents because the government’s actions and inaction had consequences that extended far beyond a single defendant. A man accused of trafficking minors was allowed to operate for years after credible allegations surfaced. Survivors were sidelined. Prior prosecutions collapsed into deals so lenient they became case studies in failure. The institutions involved moved on without a full public accounting.

The files, if released in full, would show how those outcomes were rationalized internally.

That’s why the stakes here are institutional, not sensational. These records don’t just speak to guilt or innocence. They speak to discretion, to whose warnings were taken seriously, to which risks were deemed acceptable, and to whether reputation, embarrassment, or influence shaped decisions that were supposed to be governed solely by law.

This is also why the Justice Department’s partial release is so revealing. If the documents were merely embarrassing or prurient, redaction would be sufficient. Names could be protected. Victims could be shielded. Legitimate privacy concerns could be addressed. That is standard practice, and courts routinely supervise it.

What redaction cannot do is hide patterns.

Patterns require volume, context, and timelines long enough to show repetition, hesitation, and reversal. Releasing less than o1% doesn’t just withhold information. Rather, it prevents understanding. It ensures the public never sees how decisions evolved, how often opportunities for accountability were missed, or how consistently the same justifications were used.

This is why treating the Epstein files as a scandal archive misses the point. They are closer to an audit, not of one criminal, but of the system that failed to stop him.

And audits are dangerous to institutions that prefer their errors remain isolated, their failures fragmented, and their accountability diffuse.

The question, then, is not whether the public can be trusted with these records. It’s whether the Justice Department can withstand what they reveal when read as a whole.

So far, the answer appears to be no.

Less Than 1% Is a Strategy

How Partial Compliance Neutralizes Accountability

Releasing less than 1% of the Epstein files is not an accident. It is a tactic.

In bureaucratic systems, partial compliance is often more effective than outright refusal. A flat “no” invites confrontation. A token “yes” buys time. It creates ambiguity, diffuses urgency, and gives institutions room to argue they are acting in good faith, even when the substance of compliance is missing entirely.

This is what compliance theater looks like.

By releasing a sliver of documents, the Justice Department can claim progress without producing accountability. Headlines soften. Legal pressure cools. The story becomes technical instead of urgent. The public is left arguing over process rather than confronting the fact that a court order was effectively ignored.

This tactic works because it exploits how attention functions. A full refusal is news. A partial release is a shrug. It sounds procedural and feels incremental. It encourages the assumption that the rest will come eventually, even when no timeline, inventory, or enforcement mechanism exists to ensure that it does.

Less than 1% is not a bridge to transparency. It is a pressure valve.

The strategy also shifts the burden. Instead of the government having to justify secrecy, critics are forced to prove bad faith. Instead of the department explaining why it missed a deadline, journalists and advocates are left chasing follow-up questions that can be endlessly deferred: How many documents remain? What categories exist? What is the schedule? What is being withheld and why?

None of those questions can be answered from a symbolic release. That is the point.

This approach has precedent. Agencies facing damaging disclosures often release just enough material to claim responsiveness while keeping the larger archive sealed behind claims of review, sensitivity, or inter-agency coordination. Over time, the sense of scandal fades. Court orders age, public focus shifts, and what was once a clear violation becomes an unresolved footnote.

The danger is not just that the Epstein files remain hidden. It’s that this method becomes normalized.

If releasing a fraction of a percent is treated as compliance here, in one of the most scrutinized cases in modern history, it sets a template for future cases involving government misconduct, elite protection, or institutional embarrassment. Transparency becomes performative. Accountability becomes optional. Deadlines become suggestions.

And because this strategy relies on quietness rather than confrontation, it rarely triggers consequences. There are no immediate sanctions or dramatic showdowns. Instead, there is just a slow drift away from the idea that court orders bind everyone equally.

That drift is easy to miss. It doesn’t announce itself. It shows up in math that doesn’t add up, in percentages so small they expose the intent behind them.

Less than 1% is not a mistake. It is the system signaling how much scrutiny it is willing to tolerate, and how much it expects the public to accept.

Who Benefits From Silence

Institutions Protect Themselves First

When transparency stalls, it’s worth asking who gains from the quiet, not in names or rumors, but in structure.

The primary beneficiary of non-disclosure is not any single individual. It is the institution itself.

Full release of the Epstein files would not simply revisit a disgraced financier’s crimes. It would reopen a record of prosecutorial judgment. It would expose how warnings were weighed, how credibility was assessed, and how aggressively or cautiously authority was exercised. That kind of visibility doesn’t just assign blame. It clarifies responsibility, and responsibility is expensive.

For a justice system that relies on public trust, revisiting past failures at scale carries reputational risk. It invites uncomfortable questions about consistency, independence, and whether outcomes would have differed had the defendant lacked money, lawyers, or connections. It also risks undermining the narrative that prior resolutions were reasonable at the time, a narrative institutions are deeply invested in preserving.

Silence protects that narrative.

There is also an internal logic to withholding records that extends beyond embarrassment. Transparency can constrain future discretion. Once patterns are visible — once it’s clear how often exceptions were made, how negotiations deviated from norms, how certain concerns outweighed others — it becomes harder to argue that those decisions were isolated or inevitable. Institutional memory becomes public memory.

That changes behavior, and not always in ways bureaucracies welcome.

Non-disclosure also shields the department from external scrutiny it cannot fully control. Congressional oversight, civil litigation, inspector general reviews, and public-interest lawsuits all gain leverage from documents. Records create hooks. They allow follow-up and turn abstract criticism into evidentiary questions that demand answers. Keeping the archive sealed keeps those hooks out of reach.

This is why silence is safer than transparency, even when transparency is legally required.

Importantly, this incentive structure doesn’t require coordination or conspiracy. It functions automatically. Every additional document released increases exposure, complexity, and risk. Every document withheld preserves ambiguity. When faced with that choice, institutions predictably favor the option that minimizes immediate cost, even if it deepens long-term damage.

That calculus explains why partial release is so appealing. It signals responsiveness without surrendering control. It satisfies formal demands while avoiding substantive reckoning. It allows officials to say, truthfully but misleadingly, that progress has been made.

The result is a familiar outcome: accountability diluted until it disappears.

This is not unique to the Epstein case. What makes this moment different is the clarity of the obligation and the scale of the shortfall. When less than 1% is released after a court-ordered deadline, the benefit of silence becomes unmistakable. The cost of disclosure, in the department’s own assessment, outweighed the cost of defiance.

That judgment tells us everything we need to know about where the balance currently sits, and whose interests it serves.

Congress Ordered Transparency. DOJ Ignored the Law.

This Was a Statutory Mandate, Not a Suggestion

This disclosure was not optional, and it was not discretionary. It was required by law.

Congress set a clear deadline for the release of Epstein-related records: December 19. The mandate did not ask the Justice Department to make a judgment call. It did not invite negotiation. It imposed an obligation — one rooted in legislation, not convenience — that applied regardless of whether compliance was comfortable or reputationally costly.

The U.S. Department of Justice did not meet that obligation.

By the time the deadline passed, the department had released less than 1% of the material it was required to disclose. That failure was not revealed through a press release or voluntary transparency. It surfaced because the department was forced to acknowledge its noncompliance in federal court filings, a legal setting that exists precisely because statutory mandates mean nothing if agencies can ignore them without consequence.

This distinction matters. The courts are not the source of the requirement here; they are the enforcement mechanism. Congress passed the law. DOJ violated it. The judiciary is now the arena where that violation is being exposed.

When an executive agency disregards a legislative mandate, the damage is not procedural. It is constitutional. Congress’s authority rests on the premise that its laws will be executed. When enforcement bodies decide which statutes they will honor, separation of powers becomes a theory rather than a practice.

This was not a case of unavoidable delay followed by good-faith remediation. The department did not seek a public extension. It did not publish a comprehensive inventory of withheld records. It did not provide a clear timeline for compliance. Instead, it released a symbolic fraction of documents and allowed the deadline to lapse, effectively daring the system to compel what the law already required.

That posture is a form of institutional defiance.

It signals that transparency mandates are negotiable when they threaten powerful interests. Deadlines can be missed without penalty. Statutory requirements can be reduced to suggestions if ignoring them is easier than honoring them.

If this violation stands — if Congress’s mandate is treated as optional and the courts are left to absorb the consequences — the precedent will not remain confined to the Epstein files. It will apply wherever disclosure risks embarrassment, liability, or loss of narrative control.

This is how laws hollow out, not through repeal, but through selective obedience.

The Epstein records are simply the latest test case, and once again, the system is failing it.

This Is Why Trust Collapses

Selective Transparency Teaches the Public Not to Believe

Trust in institutions doesn’t collapse because people are cynical. It collapses because patterns repeat.

When Congress passes a law requiring transparency and the Justice Department responds by releasing less than 1% of the mandated records, the message isn’t subtle. It tells the public that rules apply unevenly, aggressively enforced downward, and selectively honored upward.

For most people, this isn’t theoretical. Miss a tax deadline and penalties follow. Ignore a court notice and consequences escalate. Fail to comply with a legal requirement and the system moves quickly to enforce it. Watching the government itself ignore a statutory mandate without immediate consequence makes the disparity impossible to ignore.

This is where faith in “the process” breaks.

Secrecy doesn’t preserve trust; it destroys it. The instinct to withhold information in the name of stability almost always produces the opposite effect. When official explanations stop short, people fill the gap themselves. Rumors flourish, conspiracy narratives harden, and even legitimate outcomes become suspect, because the record that could confirm them remains hidden.

The Epstein case is a perfect example. Full transparency would narrow speculation by replacing inference with documentation. It would allow the public to distinguish between misconduct and error, between negligence and constraint. Instead, partial disclosure keeps every question open and every suspicion alive.

That outcome is not accidental. Systems that resist scrutiny often convince themselves that opacity is protective, that the public can’t be trusted with complexity. Yet what actually erodes trust is the sense that complexity is being used as cover, that deadlines are missed not because compliance is impossible, but because accountability is inconvenient.

The long-term damage is cumulative. Each instance of selective transparency lowers expectations. Each unpunished violation teaches the public to assume that future promises will be broken as well. Over time, trust doesn’t just erode. It inverts. People stop assuming good faith and start assuming concealment.

That shift is deadly for a justice system.

Courts depend on voluntary compliance. Prosecutors depend on credibility. Investigators depend on cooperation. When the public no longer believes that institutions tell the truth when it matters most, every enforcement action becomes harder, every verdict more contested, every explanation more suspect.

The irony is that this erosion harms legitimate justice far more than transparency ever could. Releasing the Epstein files would not weaken the Justice Department. It would strengthen it by acknowledging failure, clarifying responsibility, and drawing a clear line between what went wrong and what must not happen again.

Instead, the department chose silence, and silence, in cases like this, is not neutral. It is corrosive.

Legacy Media’s Soft Language Problem

When the Press Softens Language, Power Wins

The Justice Department did not “fall behind.” It did not “struggle with volume.” It did not “face delays due to complexity.”

Those phrases are choices, and they are doing damage.

When coverage describes the release of less than 1% of legally mandated records as a delay, it launders failure into process. It replaces accountability with passivity. The reader is left with the impression that something is happening — slowly, imperfectly, but earnestly — rather than confronted with the reality that the law was ignored.

This is how institutional misconduct survives scrutiny, not through censorship, but through euphemism.

Language matters because it frames consequence. A delay implies intention to comply. Noncompliance demands enforcement. By choosing the softer term, much of the press has preemptively absolved the Justice Department of the need to explain itself. The result is a story that feels technical instead of urgent, procedural instead of political, bureaucratic instead of constitutional.

That framing didn’t happen by accident.

Legacy media is structurally uncomfortable with stories that implicate the justice system as a system. Individual bad actors are safe territory. Structural failure is not. It forces editors to confront their own reliance on official sources, their past coverage decisions, and the uncomfortable possibility that trusted institutions can — and do — choose opacity over accountability when stakes rise.

So the story gets trimmed. The verbs soften. The math is mentioned without being interrogated. Less than 1% becomes a detail, not an indictment.

The effect is predictable. Readers skim. Outrage diffuses. The deadline fades. The violation is absorbed into the background noise of governance dysfunction, rather than treated as the precedent-setting act it is.

This is why independent media exists, not to sensationalize, but to say plainly what polite coverage avoids: a law was passed, a deadline was set, and the agency responsible for enforcing the law did not comply. That is not a nuance problem. It is a failure problem.

When the press refuses to name that failure clearly, it becomes part of the mechanism that enables it, not because journalists are malicious, but because institutional deference is baked into the culture. Access is rewarded. Confrontation is not. Stories that threaten to destabilize “trust in the system” are often smoothed until they no longer threaten anything at all.

However, trust isn’t preserved by soft language. It’s preserved by accuracy.

Calling noncompliance a delay doesn’t protect the Justice Department. It protects the illusion that accountability still functions the way we’re told it does. That illusion is far more fragile and far more dangerous than any uncomfortable truth buried in the Epstein files.

If this story feels quieter than it should, it’s because it’s being quieted.

And that silence, like the one coming from the Justice Department itself, is a choice.

Epstein as a Stress Test the System Keeps Failing

Every Time the System Is Tested, It Retreats

The Epstein case didn’t break the system. It revealed it.

Over and over again, this case has served as a stress test, and each time, the result has been the same. Deference to power. Fragmented accountability. Institutional retreat disguised as discretion.

In 2008, the system failed quietly. A federal prosecution collapsed into a plea deal so lenient it became infamous, justified after the fact as pragmatic judgment. Victims were sidelined. The public was told the outcome was reasonable, even necessary.

In 2019, the system failed loudly. Epstein was arrested, the case reopened, and long-buried questions resurfaced. Then he died in federal custody under circumstances that should have triggered radical transparency. Instead, explanations arrived slowly, accountability diffused quickly, and attention moved on before a full reckoning could occur.

Now, the system is failing administratively, and that may be the most dangerous failure yet.

This time, there is no plea deal to debate and no single death to explain away. There is a clear legislative mandate, a firm deadline, and a measurable outcome. Less than 1%. No ambiguity. No gray area. Just a number that exposes the decision behind it.

What connects all three moments is not Epstein himself. It’s the institutional instinct to contain damage rather than confront it.

Each phase followed the same arc:

A problem emerges that threatens elite confidence in the justice system

Transparency is promised, but tightly controlled

Accountability is narrowed to the smallest possible scope

The system declares closure without full exposure

Each time, the lesson absorbed internally is the same: withstand the pressure long enough, and it will pass.

That’s why this moment matters more than the last. The question is no longer whether the system made mistakes. It’s whether it is capable of acknowledging them without being forced, and whether it will honor transparency obligations even when there is no immediate scandal driving attention.

So far, the answer is no.

The refusal to fully release the Epstein files is not a continuation of past failures; it is their institutionalization. It signals that lessons were not learned — only refined. That resistance can be quieter, slower, more procedural, and therefore more effective.

This is how accountability erosion becomes policy.

The Epstein case keeps returning not because the facts change, but because the system’s response does not. Every iteration lowers the bar. Every partial disclosure resets expectations downward. Every missed opportunity teaches future officials that survival depends not on honesty, but on endurance.

Endurance, as this case shows, is something power has in abundance.

What happens next will determine whether this pattern finally breaks or whether Epstein becomes the template for how elite accountability fails in America, one generation at a time.

What Real Compliance Would Look Like

Transparency Has a Playbook. DOJ Didn’t Use It

Real compliance is not mysterious. It is not abstract, and it does not require heroics.

If the Justice Department intended to follow the law, there is a clear, well-established path it could take, one used routinely in complex cases involving sensitive material, national security, and victim protection. None of this requires improvisation. It requires will.

First, real compliance starts with scope. The department would publicly acknowledge the full universe of Epstein-related records in its possession. This means not their contents, but their existence. An inventory — categories, date ranges, originating offices — is the minimum requirement for transparency. Without it, the public cannot even know what is being withheld, let alone why.

Second, it requires a timeline. Open-ended promises are not compliance. A schedule with firm milestones is. Courts and agencies manage rolling disclosures every day. Stating when batches will be released, and what percentage of the total they represent, transforms transparency from theater into process.

Third, it requires disciplined redaction, not blanket secrecy. Legitimate concerns exist, such as protecting survivors, safeguarding ongoing investigations, and shielding personal data. Those concerns justify redactions. They do not justify suppression. The law already provides tools to balance disclosure with protection, and courts routinely supervise that balance.

Fourth, real compliance demands accountability for delay. If the department cannot meet statutory deadlines, it must publicly explain why, specifically, and, if necessary, under oath. Vague references to volume or complexity are not explanations. They are placeholders.

Finally, compliance means acceptance of oversight. Inspectors general, courts, and Congress exist to ensure that agencies do not become judges of their own conduct. Transparency without oversight is performative. Oversight without documents is impossible.

None of this would weaken the Justice Department. It would strengthen it. It would draw a clear line between past failures and present standards. It would demonstrate that institutional legitimacy comes not from perfection, but from correction.

What the department has offered instead is the opposite: silence in place of inventory, symbolism in place of substance, and discretion in place of obligation.

That choice has consequences.

When agencies decide that transparency is something to be rationed, rather than honored, the public learns a dangerous lesson: that accountability is not a right, but a favor granted only when it no longer threatens power.

Real compliance would prove otherwise.

So far, the Justice Department has not tried.

Power Still Writes Its Own Rules

The Rules Are Only Binding Until Power Is Threatened

The most damning fact in this entire episode is not hidden in the Epstein files. It’s right on the surface.

Congress passed a law requiring transparency. A deadline was set. The Justice Department released less than 1% of the required records. Nothing happened.

There have been no sanctions, emergency hearings, or forced timetable. Instead, there has been only quiet acceptance that the system charged with enforcing the law chose not to follow it and was allowed to move on.

That outcome tells you exactly how power operates when it is threatened.

This was not a failure of capacity. The Justice Department handles disclosures involving terrorism, organized crime, classified intelligence, and mass-casualty investigations. It knows how to inventory records. It knows how to redact responsibly. It knows how to meet deadlines or ask for relief when it cannot. What it chose not to do here was comply.

That choice exposes the real hierarchy. Laws are binding until they become inconvenient. Transparency is celebrated until it risks exposure. Accountability is demanded until it points upward.

The Epstein case keeps proving the same point because it occupies a unique position in the American psyche. It touches wealth, influence, prosecutors, politicians, institutions, and victims all at once. It is the rare case where the justice system is asked to examine itself in public.

Each time, it flinches.

The refusal to release the Epstein files in full is not about protecting the dead. It is about protecting the living, especially institutions that fear what a complete record would show about how decisions were made, whose voices mattered, and whose did not.

This is how trust is finally lost, not in a single scandal, but in the accumulation of moments where the public sees the rules bend and realizes they were never meant to apply evenly.

The danger isn’t that people become angry. It’s that they stop believing accountability is possible at all.

That is the cost of silence, of selective transparency, and of allowing power to write its own rules while insisting the rest of the country follow them.

The Epstein files are still sealed. The message is already public.

Coffman Chronicle — Support Independent Media

If this piece made something click, that wasn’t an accident. Independent journalism exists to follow power after the headlines fade, to track patterns institutions hope you won’t notice, and to put the receipts on the table when transparency quietly disappears.

If you value reporting that doesn’t flinch, doesn’t soften language, and doesn’t stop when things get uncomfortable, consider becoming a paid subscriber.

Your support keeps this work alive and keeps these stories from being buried.

Sources:

“US Justice Department Releases Heavily Redacted Cache of Jeffrey Epstein Files.” The Guardian, December 19, 2025.

“Outrage and Legal Threats: Trump Justice Department Slammed After Limited Epstein Files Release.” The Guardian, December 20, 2025.

“The DoJ Failed to Comply with Epstein Files Law – Can Congress Do Anything?” The Guardian, December 21, 2025.

“Schumer to Ask Senate to Back Legal Action Over Partial Epstein Files Release.” The Guardian, December 22, 2025.

“US Legislators Say Justice Department Is Violating Law by Not Releasing All Epstein Files.” The Guardian, December 19, 2025.

“Less Than 1% of the Epstein Files Have Been Released, DOJ Says.” TIME, January 6, 2026.

“US Congressmen Ask Judge to Appoint Official to Force Release of All Epstein Files.” The Guardian, January 8, 2026.

Epstein Files Transparency Act, Pub. L. 119–38 (2025). GovInfo.

The Epstein files release is the one issue that unites democrats, conservatives, MAGA, independents etc. It's the sledgehammer that we need to use to pound this murderous regime into submission.

Epstein files must be released fully!