The Memorial Day Origin Story They Don’t Teach

Like most American myths, the truth is much different than you've been led to believe.

Every year, Americans mark Memorial Day with parades, speeches, and family gatherings. For many, it’s a long weekend filled with sales and barbecues. But beneath the red, white, and blue bunting lies a rarely told story, one that begins not with generals or presidents but with newly freed African Americans determined to honor the dead.

We just hit 13,000 subscribers—thank you!

Get exclusive analysis and fearless reporting you won’t find in corporate media.

A Cemetery Where Horses Once Ran

The setting was Charleston, South Carolina. The Civil War had just ended, and the city still bore the scars of the Confederacy’s collapse. In the midst of the ruins stood the Washington Race Course, a former horse track that had been converted into a Confederate prison camp. There, more than 260 Union soldiers, many of them captured and starved, had died and been buried in a mass grave behind the grandstand.

What happened next was neither commanded nor expected. It was, quite simply, an act of profound human dignity.

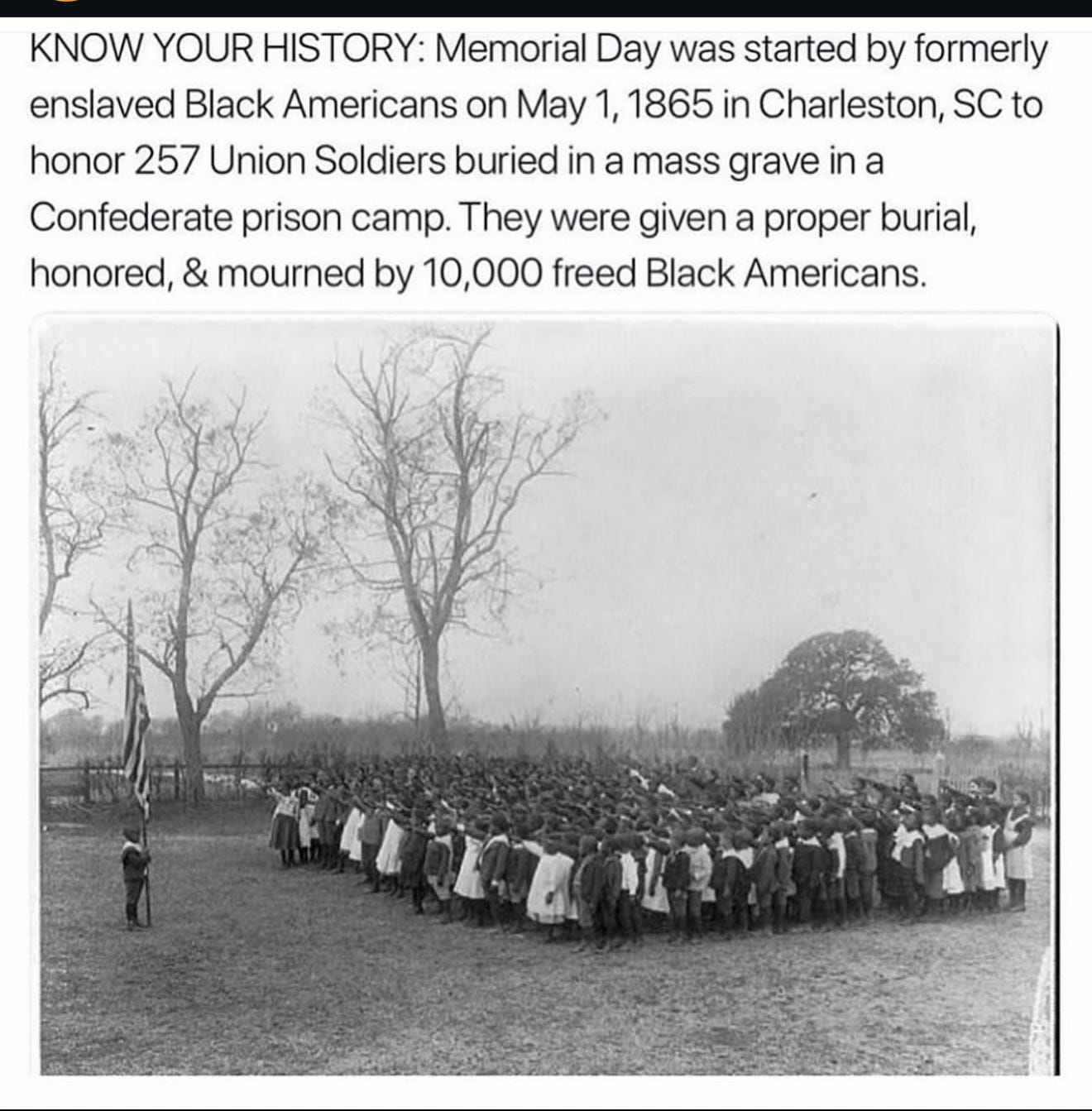

On May 1, 1865, thousands of freed Black men, women, and children gathered at the site. Having exhumed the mass grave, they reburied each soldier with care, built a fence around the new cemetery, and adorned it with an arch that read “Martyrs of the Race Course.”

Then, they held a parade of over 10,000 people, including 3,000 Black schoolchildren carrying flowers and singing hymns. Black ministers preached. Union troops marched. The newly emancipated honored the dead not just as fallen soldiers, but as liberators.

It was a spontaneous, community-led Memorial Day before the nation even gave the tradition a name.

Burying the Story Along with the Dead

Despite its magnitude, this event was largely forgotten by the mainstream historical record. For over a century, Memorial Day's origin story focused almost exclusively on General John A. Logan, the white commander of a Union veterans’ group, who issued General Order No. 11 in 1868, designating May 30 as a national day of remembrance.

Logan’s declaration certainly helped formalize the holiday, but it didn’t start it.

It wasn’t until the late 1990s that this long-buried history resurfaced. Historian David W. Blight, while researching post–Civil War memory, came across a firsthand account from 19th-century journalist and abolitionist James Redpath. Blight recognized what had been overlooked for generations: the first organized Decoration Day had taken place in Charleston, led by those newly freed from bondage.

Blight called the Charleston event “the first Decoration Day.” In his words, “What you have there is Black Americans recently freed from slavery announcing to the world with their flowers, their feet, and their songs what the war had meant to them.”

Memory as Power

The Charleston commemoration wasn’t just a tribute to the dead. It was a political act, a bold claim on citizenship, sacrifice, and the right to be remembered.

It declared that freedom had been earned with blood, and that Black Americans had a rightful place in the national narrative of liberty.

They were not asking to be remembered. They were insisting that the country reckon with who had died, who had suffered, and who had built the very democracy being commemorated.

It also challenged a nation eager to move on. As the Reconstruction era gave way to Jim Crow, this founding moment and the Black agency behind it were quietly erased from the whitewashed story of America.

Memorial Day became a civic ritual, but not an inclusive one.

Why It Matters Now

This history matters today more than ever.

At a time when Black history is being banned from classrooms, when books are pulled off shelves, and when the memory of slavery is treated like a taboo rather than a truth, remembering the real origins of Memorial Day is an act of resistance.

It’s also a reminder that the fight for freedom didn’t end with emancipation and that the duty to remember belongs to all of us, not just those in uniform or elected office.

So as we gather around grills this weekend, we owe it to the dead and the living to remember who truly helped give birth to this day.

Take Action

This Memorial Day, honor the full story:

Tell someone this history, especially if they’ve never heard it.

Encourage local schools and libraries to include the Charleston commemoration in their curriculum.

Support efforts to protect Black history from being legislated out of public memory.

Most importantly, never forget that the first Memorial Day wasn’t just about mourning, it was about meaning.

It was a declaration of Black dignity and a demand that America remember who made it free.

We just hit 13,000 subscribers—thank you!

Get exclusive analysis and fearless reporting you won’t find in corporate media.

Bibliography:

Blight, David W. Race and Reunion: The Civil War in American Memory. Harvard University Press, 2001.

Blight, David W. “Forgetting Why We Remember.” The New York Times, May 29, 2011.

Redpath, James. The Roving Editor, or Talks with Slaves in Southern States. A.B. Burdick, 1859.

"Memorial Day: A Commemoration." National Archives, May 25, 2018.

"Was Memorial Day Created By Former Slaves to Honor Union War Dead?" Snopes.com, May 30, 2011.

Wallace-Sanders, Kimberly. Still Picture: Black Feminist Reflections on Memory, Mourning, and Memorial. Duke University Press, 2022.

Litwack, Leon F. Been in the Storm So Long: The Aftermath of Slavery. Vintage Books, 1980.

Janney, Caroline E. Remembering the Civil War: Reunion and the Limits of Reconciliation. University of North Carolina Press, 2013.

Savage, Kirk. Standing Soldiers, Kneeling Slaves: Race, War, and Monument in Nineteenth-Century America. Princeton University Press, 1997.

DuBois, W.E.B. Black Reconstruction in America 1860–1880. Free Press, 1998 (originally published 1935).

i didn't know that.

Until I read this article just now, I had never heard this account of the first Memorial Day. Thank you.